Medieval

Medieval

History

Background

Medieval History

- Introduction

- What Hospitals were there in Medieval Norwich?

- Who Founded St.Giles', and Why?

- What was Purgatory?

- Did Patrons advertise?

- Who was St.Giles?

- What were the rules at St.Giles'

- Where did the Money and Land come from?

Buildings and Changes

Introduction

This part of the site is designed to guide you through the medieval history of the Great Hospital (or St Giles', as it was known in the Middle Ages). It tells you about Bishop Walter Suffield, and why he founded the hospital.

However, click here if you just want to see a video of what the hospital looked like in this period. You can even stop the video and find out more as you explore.

[top]

What Hospitals were there in Medieval Norwich?

During the period following the Norman Conquest in 1066, Norwich was vibrant and expanding, but it also had a growing influx of malnourished, destitute and physically disabled paupers. These were catered for in its hospitals, which began to appear in the last years of the eleventh century.

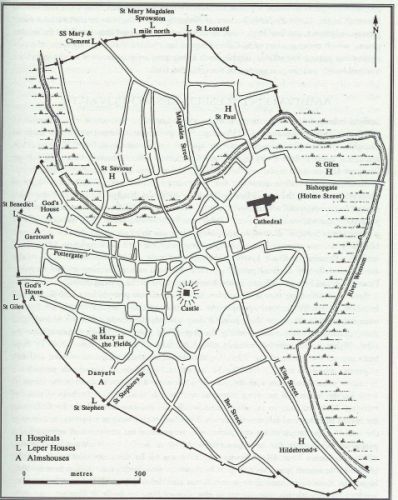

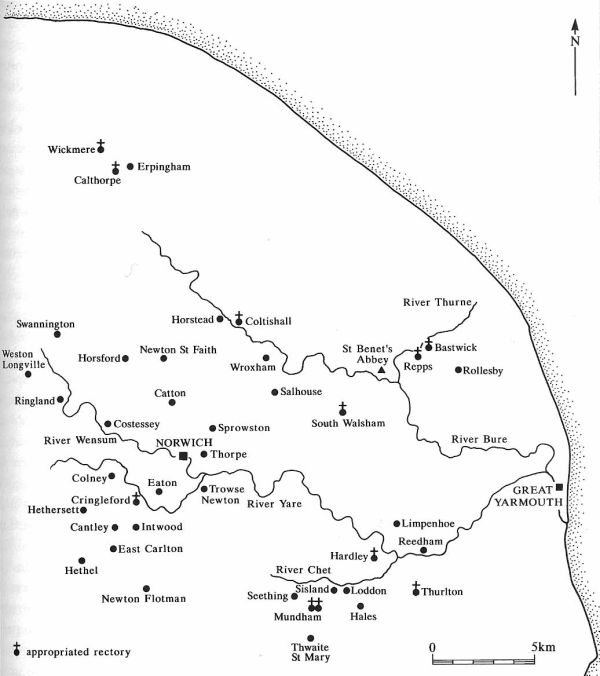

The still imposing stone leper house of St Mary Magdalen, for instance, was one of the first; this was followed by the hospital church of St Paul, which had been erected to care for needy travellers as well as the 'sick, infirm, and child-bearing'. Over the next century, a further four (out of an eventual five) small communal leper houses were built on the roads leading into Norwich (see map).

Indeed, hospitals were mainly suburban developments, located just outside or immediately within city walls, on the outskirts of expanding centres such as York and Norwich. Practical considerations dictated this choice of site, as land was often cheaper, and there was more space for gardens and food production. However, life on the margins could have its drawbacks, and the medieval hospital could sometimes be an unpleasant, even risky place to live. In the Middle Ages, 'undesirables', such as the poor and diseased, congregated together at the rougher end of the medieval townscape, often outside the walls. Perhaps this explains why at St Giles' in 1477-78 money was spent on locks, bolts and keys - unlike the poor sick, thieves and vagabonds were not welcomed.

Pictured above: Map of the hospitals of medieval Norwich, taken from C. Rawcliffe, Medicine for the Soul: The Life, Death and Resurrection of and English Medieval Hospital. St Giles's, Norwich, c. 1249-1550 (Stroud, 1999), p. 3.

While land in the suburbs may have been cheaper, it was often of relatively poor quality. The precinct of St Giles', for instance, encompassed ten acres, and contained meadows, gardens, orchards, fishponds, workshops and a brewery. Even so, a considerable expanse of the meadows on the bend of the river remained marshy and wet throughout the medieval period. In fact, sometimes flood water even reached the hospital infirmary.

[top]

Who Founded St.Giles', and Why?

Pictured above: The Great Hospital sign. Photographer: C. Bonfield

Bishop Walter Suffield founded St Giles' hospital around 1249, partly out of sympathy for the poor and sick, but also, he claimed, to secure the remission of his sins.

Founders or benefactors endowed hospitals as works of charity which relieved the suffering of less-fortunate people. Whether for lepers or the sick and aged poor, they were beacons of charity that shone in the urban landscape. When the sick entered the sacred environment hospital, it was believed that their burden of sin would be erased. Yet, more importantly for rich men like Bishop Suffield, founding a hospital was thought to guarantee their own spiritual health. In fact, a patron, by supplying the necessary funds, hoped to ease his or her passage through Purgatory.

[top]

What was Purgatory and why would Bishop Suffield have wanted to spend less time there?

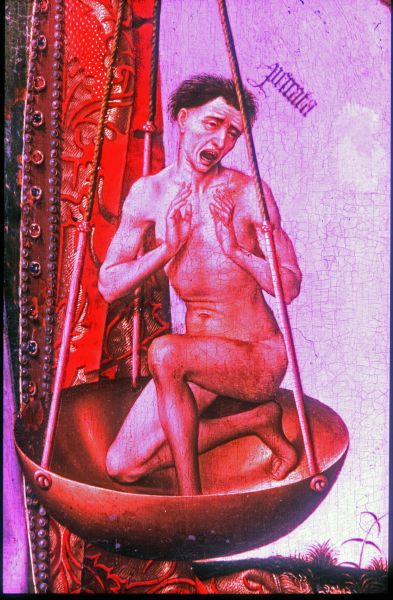

In the Middle Ages, the Church taught that at the Last Judgment all souls would be weighed in St Michael's scales. A few had already secured a place in heaven because of their sanctity, while others were damned and sent directly to hell, but most were destined to pass through a temporary stage called Purgatory, before finally joining God and the saints.

Purgatory was far from pleasant: as its name suggests, it was a place of purification. Although the sacrament of baptism had washed away Original Sin, any unabsolved sins committed during a person's lifetime still had to be erased from his or her soul. The methods were little different from those deployed (for all eternity) in hell.

Pictured above: Museum of the Hôtel Dieu, Beaune- a sinner being weighed in St Michael's scales

Unlike the poor, who were "blessed ... in spirit for theirs is the kingdom of heaven" (Matthew 5: 3), the rich enjoyed no such reassurance. Whereas their hoards of cash might have secured a high rate of illicit interest, their souls had been saddled with a large spiritual debt which required a lengthy stay in Purgatory. Indeed, as Christ had warned His disciples, "it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for one who is rich to enter the kingdom of heaven" (Matthew 19:24).

It was believed, however, that time spent in Purgatory could be shortened if mortals would pray for the tortured soul. Establishing a hospital was considered an effective means of securing perpetual prayers - poor inmates would be so grateful for the help that they received that they would happily intercede for the departed soul of their generous patron.

In addition, works of charity helped to tip St Michael's scales in the right direction. Indeed, the Church taught that there were Seven Comfortable Works (feeding the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, giving shelter to strangers, clothing the naked, visiting the sick, visiting the imprisoned and, later, burying the dead). Those who had done these good deeds (such as a patron of a medieval hospital) were destined to Heaven. Those who had not, however, were to be cast "into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels" (Matthew 25: 41-42).

Hospitals were a charitable investment which not only offered physical comfort and care to those on earth, but also paid dividends in the next life. This did not mean that a patron such as Bishop Suffield did not care about his patients' welfare, but that there was a reciprocal agreement. In return for providing the needy with help, he expected prayers to be said for his soul.

Pictured above: NRO NCR 24B 1/2 - Bishop Walter Suffield's seal from his will.

[top]

Did Patrons advertise?

Just in case patients might forget who to pray for, Bishop Suffield, and subsequent masters and benefactors, made sure that their 'image' was prominently displayed in the hospital, much in the same way that sponsors pay for an appropriate logo to be shown at football matches and other events today.

They hoped that such visual reminders would prompt the prayers and religious services necessary to speed their souls through the torments of Purgatory.

Pictured above: The patrons' archway Photographer: C. Bonfield

John Selot (master, c. 1455-1479), with assistance from Bishop Walter Lyhart (c. 1446-1472), built the hospital cloisters (click here to see a video of the cloisters). Lyhart's coat of arms may still be seen in the right hand spandrel of the arch in the doorway (now bricked up) which led in the Middle Ages from the east side of the cloister to the chapter house. Below are the arms of another notable benefactor, prior Molet of the neighbouring Cathedral Priory. A shield baring his heraldry is still to be found in the restructured nave of the hospital church, which was divided into three bays by columns, and was thus on an ideal place to display the heraldic trappings of wealthy patrons. Prominent among these were the arms of Bishop Goldwell, to whom the hospital owed so much .

Pictured above: The Coat of Arms of Bishop Goldwell Photographer: C. Bonfield

[top]

Who was St.Giles, and why did Bishop Suffield name his Hospital after the saint?

In Medieval England, confessor saints, like St Giles, proved to be a popular choice. With their ears on earth and their tongues in the heavenly court, they had a direct line to God and His cornucopia of blessings. Their relics were also thought to have had the power to cure. That is why many people went on pilgrimage - they went to see/ touch/taste their chosen saint in the hope that they, or a close family member or friend, would be cured.

St Margaret, shown here emerging unscathed from the belly of a dragon, was the patron saint of women in childbirth. A carving of her and her dragon can still be seen today on a bench end in St Helen's church. John Hecker, an early sixteenth-century master, had his initials (HEC) carved underneath.

Pictured above: Photograph of bench end depicting St.Margaret emerging from the dragon. Photographer: C. Bonfield.

Hospital chapels were often dedicated to saints who were well known for their healing powers, such as St Bartholomew (skin diseases) and St Leonard (nursing mothers). St Giles (died c. 710) was the patron saint of lepers, nursing mothers and cripples, but he was also reputed to have given away all his possessions to the poor and to have cared for the sick. More importantly, it was believed that St Giles had especial sympathy for sinners who wished to repent and for people who died without first confessing their sins (a terrible omission which effectively guaranteed a very long term in Purgatory, if not eternal damnation).

[top]

What were the rules at St.Giles'

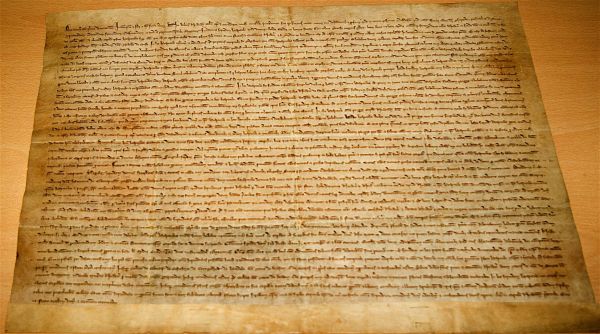

When Bishop Suffield founded his hospital, he created rules which he wanted everyone to follow. These were then recorded in the hospital's foundation charter. These rules were later changed and approved, but never altered significantly until the sixteenth century.

Pictured above: NRO, NCR 24B/1 - the foundation charter.

Click here to see the foundation charter in closer detail. You can also read an English translation which incorporates some later changes.

As you can see, there were quite a few rules and regulations, but most dealt with the master, the brethren and sisters, patients, and those religious services which Bishop Suffield wanted to take place. Here are ten which might interest you:

- There was to be a master to take good care of the hospital, and to work for the remission of Bishop Suffield's sins (3).

- There were to be at least three or four women, aged over fifty, who were to change the sheets and take care of the sick (5)

- Everyone had to get up at the crack of dawn to say prayers (7)

- There was to be a weekly mass in honour of St Giles (9)

- There were to be thirty beds or more (11)

- Thirteen poor men were to fed daily (14)

- There was to be a poor box from which poor people passing by could receive alms and charitable assistance (15)

- The sisters were to sleep in a separate dormitory (24)

- No women were allowed to stay in the hospital as patients (32)

- There was to be a free chantry in the chapel of the hospital (42)

[top]

Where did the Money and land come from?

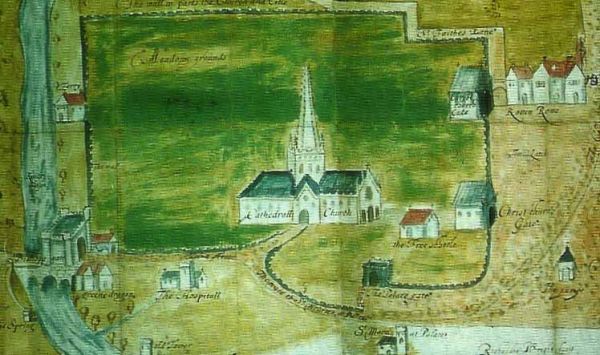

Bishop Suffield's first and second drafts of the foundation charter stated that the hospital "extends to the street opposite the church of St Helen, beneath the wall of the court of the prior and convent of Norwich. And in width it stretches to the north as far as the bank of the great river flowing by the said city. And in length it stretches towards the bridge called bishop's bridge."

Pictured above: NRO, ACC 1997/215 - a map of Norwich showing the hospital, bishop's bridge and the cathedral.

Suffield also granted the hospital revenues from the churches of Calthorpe, Costessey, Cringleford, St Mary (South) Walsham, Hardley and Seething. During the 1320s, these raised a minimum of between £30 and £40 a year in cash. But this was not enough. A regular, secure and adequate income was essential from the outset if the hospital was to meet all its obligations. Thus, the first few decades of the hospital's existence were marked by a flurry of acquisitions and exchanges of land which provided the financial income necessary to care for patients, pay staff and purchase furniture and vestments. In fact, local people gave their support to the hospital from the outset, with many contributing small pieces of land, tenements or rents to augment the hospital's coffers.

Pictured above: Map of the Norfolk estates of St Giles' hospital, taken from C. Rawcliffe, Medicine for the Soul: The Life, Death and Resurrection of an English Medieval Hospital. St Giles's, Norwich, c. 1249-1550 (Stroud, 1999), p. 71.

A substantial boost was received in 1272. A leading Norwich citizen, William Dunwich, left money and property to support five infirm people in the hospital. Other holdings in Norwich were acquired through William Dunwich's personal interest in the new hospital, and through the generosity of a neighbouring landowner, Lady Isabel de Cressy. Throughout the following centuries, new pieces of land and properties were accumulated. Some donations were substantial, such as the £100 given by a priest named Thomas de Preston in 1340, but other gifts consisted of just a few pennies.

Click here to read a list of the major acquisitions of property by St Giles'

Strangely, in our eyes, caring for the sick or poor residents was not always the primary concern of people who supported the hospital. Many of the grants or gifts were intended to fund chantry priests whose job was to pray for the donor's soul. For instance, when William Dunwich endowed a perpetual chantry of one priest in 1271, he decreed that the priest was to sing a mass of the Blessed Virgin everyday, while calling upon the patients lying in bed to remember him when they prayed.

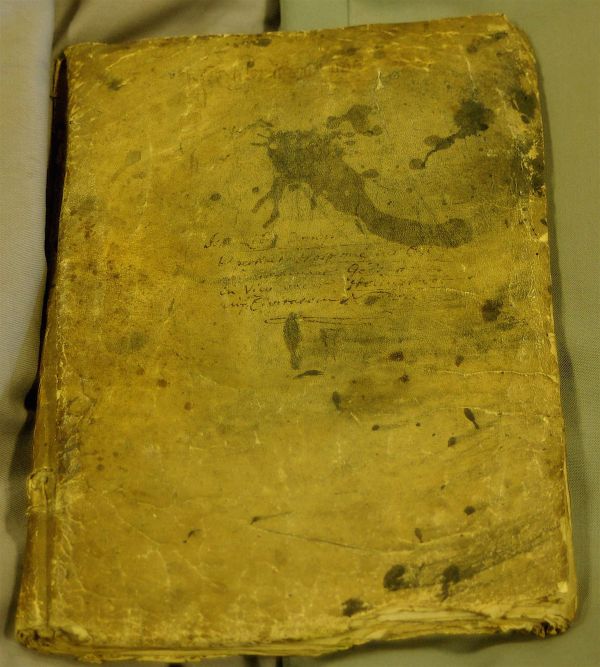

At St Giles', some 260 grants, purchases, exchanges and quitclaims, mostly during the second half of the thirteenth century and early 1300s, were recorded in the accessible format of a cartulary, known as the Liber Domus Dei (Book of God's House).

Pictured above: the Liber Domus Dei (Book of God's House) - NRO, NCR 24B/48.

Despite all the financial help the hospital received, balancing the books was never easy. Apart from money spent on caring for residents, costs included repairs to buildings, the collection of debts, payment of salaries and other regular outgoings. Worsening economic circumstances after the ravages of the Black Death (1348) affected land-owners, including the hospital, and by the mid-sixteenth century the master of St Giles' was under increasing financial pressure just to maintain, let alone expand, the level of care afforded to the poor.

This helps to explain why, towards the end of the fourteenth century, the hospital handed over to the civic authorities a riverside tower which was later called the 'cow' or 'dungeon' tower. In so doing the brethren rid themselves of any financial responsibility for the upkeep of a crucial link in the city's defences.

Pictured above: The 'Cow' tower which stood at the north-eastern extremity of the hospital precinct, on a bend in the river Wensum. Photographer: C. Bonfield.

[top]