Introduction

This part of the site is designed to guide you through the different parts of St Giles' hospital. It will explain when buildings were added and when they were enlarged or otherwise changed. It will also discuss the impact of the Black Death, and how this affected the appearance of the hospital.

To familiarise yourself with the hospital buildings,we suggest that you take a look at this video first - it shows you the exterior of the hospital as it is today. You should then look at the next video, which illustrates how the hospital has changed over time. You can always come back to read this section later.

[top]

What buildings were there?

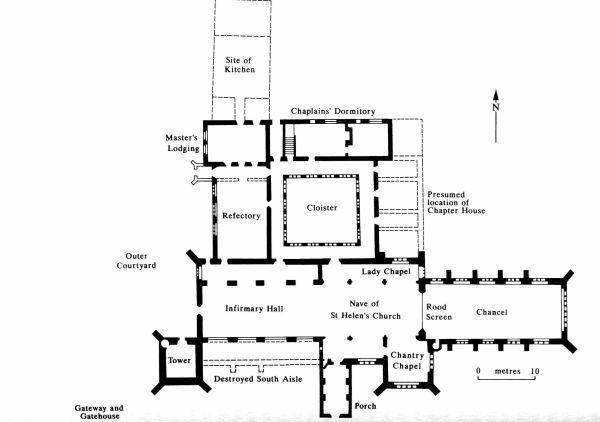

It is a good idea of begin with the ground plan of St Giles' - it will help to make more sense of where things are:

Pictured above: Ground plan of St Giles' hospital, taken from C. Rawcliffe, Medicine for the Soul: The Life, Death and Resurrection of an English Medieval Hospital. St Giles's, Norwich, c. 1249-1550 (Stroud, 1999), p. 62.

Now turn to this picture of St Giles' as it looks today. This will help you to understand what parts of the hospital were built, and when.

Pictured above: The south front of St Giles; seen from what, before 1270, would have been the approximate site of St Helen's church in the cathedral precinct. Photographer: C. Bonfield)

From right to left are:

- The medieval chancel, constructed in the 1380s and walled off as a separate ward for poor women in c. 1570

- Bishop Goldwell's late fifteenth-century chantry chapel in the south transept of the medieval nave, which was largely rebuilt at the same time as the chancel, and from c. 1547 onwards served as a parish church

- The porch, which was surmounted in the Middle Ages by another chantry chapel

- The late fourteenth-century infirmary, which lost its south aisle in Kett's rebellion and became a separate ward for poor men during the reign of Queen Elizabeth

- Archdeacon Derlynton's bell tower, completed in 1397, at the end of an ambitious architectural programme.

Now let's take a closer look

[top]

What was the chancel like?

Pictured above: The chancel as it appears today. If you want to see a video of what the upper floor looks like, click here.

By the fourteenth century, a long and imposing chancel had been built (it was finished around 1383). Over 25 metres and five bays in length, it constituted a major extension to the existing building, which was originally much smaller, and was reserved as a sacred space for the clergy and choristers. Think of the chancel as the intensive care ward of a hospital today - of course, there were no surgeons or operations, but this is where the priest celebrated Mass and conducted other religious services at the high altar.

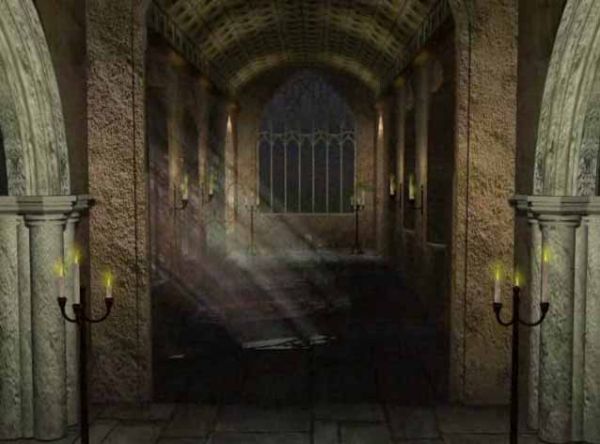

Since the east and west ends of the nave were completely walled off during the sixteenth century, it is easy to underestimate the impact of the original design. Compare, for instance, the first picture, which shows the view from the nave to the chancel as it appears today, and the second picture, suggesting how it might have looked in the later Middle Ages.

Trying to imagine how the chancel would have appeared in the fifteenth century is made even harder by the fact that sweeping alterations introduced by the civic authorities at various points after 1548 resulted in the construction of a discrete upper-storey for women.

Pictured above: A photograph of how the chancel looks today. Photographer: C. Bonfield.

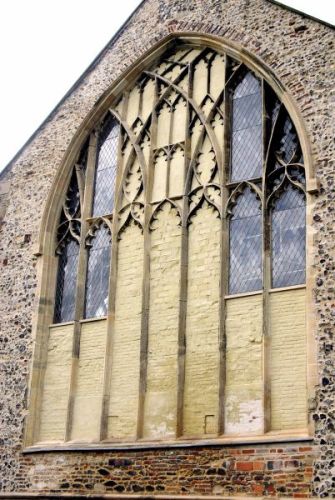

As you can see, the chancel had an impressively tall window at the east end (now bricked up and partly blocked by a chimney). In the Middle Ages, this must have flooded the room with colour from the stained glass and light, making the building feel spacious and airy. The picture below shows how very different the window looks today.

Photograph of the chancel window from the exterior. Photographer: C. Bonfield

The medieval chancel was also furnished with a wonderful chestnut ceiling, lavishly decorated with at least 252 panels, each depicting a black eagle with outspread wings, arched claws, a red beak and a long tongue.

Pictured above: The 'Eagle' ceiling in the new chancel. Photographer: C. Bonfield

The eagles were almost certainly painted in honour of Anne of Bohemia, who visited Norwich in 1383 with her husband, King Richard II. Since the rebuilding programmed had by then run short of funds, she probably stepped in with a handsome donation. Hospital chapels would often be profusely decorated with stained glass windows, elaborate ceilings, carved bosses and painting, all of which provided constant reminders of the generous patron.

Pictured above: A close up of one of the eagles in the chancel roof. Photographer: C. Bonfield

Building a new chancel was not cheap, and required the support of wealthy benefactors. It is thought that a substantial amount of money for the work came from Bishop Henry Despesner. Yet, whoever settled the bill, there can be no doubt that the chancel was a major building project, demonstrating the highest levels of architectural patronage.

[top]

What was Bishop Goldwell's chantry?

James Goldwell, Bishop of Norwich (1472-1499), almost certainly paid for this magnificent chantry chapel, where mass was to be celebrated for his immortal soul. Although he left £400 for the support a magnificent chantry in the cathedral, he apparently had some reservations concerning the monks' readiness to offer prayers and masses on his behalf. The hospital appeared a reliable choice for hedging his spiritual investment.

Pictured above: The chantry as it appears today.

The ceiling was decorated with two rings of bosses, sixteen on the outside, and eight on the inside. These too reflect the spiritual nature of the care on offer in the nearby infirmary. In the centre was a larger boss, depicting the coronation of the Virign. The other bosses illustrate well-known incidents from the life of Christ; his mother, Mary, and his grandmother, St Anne, were also represented, along with each of the twelve apostles and Saint Edward, Saint Edmund, Saint Katherine and Saint Margaret (all of whom were popular in East Anglia). Similar images quite probably appeared in the stained glass, which was destroyed by Protestant reformers.

If you want to learn more about the bosses, click here.

Pictured above: The 'inner ring' of bosses from the chantry chapel roof. Photographer: C. Bonfield.

[top]

What was the Infirmary hall like?

Pictured above: How the infirmary hall looks today

The construction of the chancel and rebuilding of the nave in the 1380s probably coincided with the construction of a new infirmary hall. With four bays, a great west window and north and south aisles 20m in length, the hall alone represented a major undertaking. It could have easily accommodated about sixteen beds; each of which was, as we have seen, equipped with all the necessary linen.

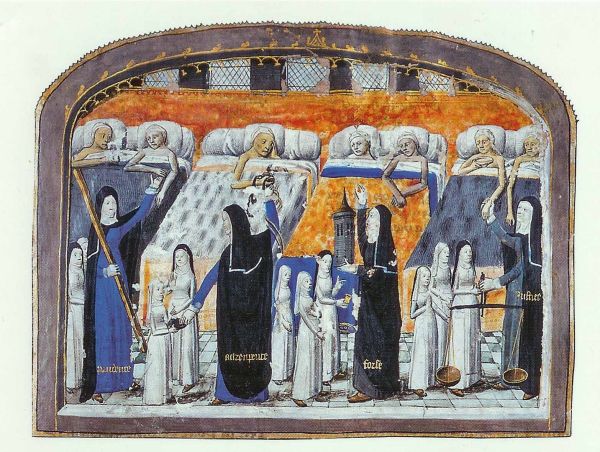

This illumination depicts the layout of any sizeable open ward infirmary: the shared beds are well furnished with covers and pillows; draughts are excluded by hangings; and windows let in light. The sick are also cared for by four professed sisters, who in this instance personify the Virtues of Prudence, Temperance, Fortitude and Justice.

Pictured above: Livre de Vie Active, Musée de l'Assistance Publique, Paris.

It is now quite difficult to envisage what the infirmary of St Giles' would have looked like; alterations made after 1548 resulted in the construction of a discrete upper-storey ward for poor men, and a wall was inserted between the aisle and nave. However, if you examine the picture below, which looks from the nave into the infirmary, you can see how it might have appeared in the Middle Ages when the central aisle opened directly, via a great archway, into the nave. This would have enabled patients to hear the priest say Mass in the chancel, as well as the sound of the choir.

Pictured above: How the infirmary might have looked in the Middle Ages.

Stained glass windows, depicting important religious figures and, of course, the patrons, offered a multitude of benefits. In an infirmary, an airy and light environment, which was believed to offer health benefits, was especially important. But, by illuminating the ward with images that had an underlying spiritual symbolism, windows also contributed towards the holistic environment of care available in medieval English hospitals.

Just like the window in the chancel, the great window at the west end of the infirmary (now partially blocked up) would have flooded the building with light, as well as colour. The mullioned windows were introduced after the creation of the men's ward.

Pictured above: Photograph of the Infirmary window from outside. Photographer: C. Bonfield

[top]

When was the Bell Tower built?

Pictured above: The bell tower at St Giles's hospital

Accounts kept by the hospital reveal that the bell tower was built at a cost of almost £100, much of which was met by John Derlyngton who was master in 1372 and subsequently occupied an important position in the diocese. Four large bells were tolled during the funerals and memorial services of benefactors, despatching their souls on a speedy journey through Purgatory. Norfolk churches are famous for their late medieval bell towers, and the hospital clearly wished to make its own mark on the city's skyline.

The ritual of the Mass was also enhanced by the sound of bells. Bells were rung just before the elevation of the Host to warn worshippers to look up because the moment of consecration and elevation was near. Indeed, they were heard regularly throughout the hospital day, instilling a sense of discipline and order as well as marking the time. The hospital statues, for instance, noted that "all shall rise in the morning at dawn when the great bell strikes".

The ringing of bells was carefully ordered in a clear set of rules known as the Use of the Church of Salisbury (Sarum rite). The Use of Sarum was the most important of the secular liturgies of medieval Britain. It was extremely popular, and many hospitals, including St Giles', either followed it or at least owned a copy.

[top]

Why did Patrons want to add buildings?

The new buildings, and the chancel in particular, provided the appropriate setting (and space) for the constantly developing ritual and increasingly elaborate religious services that both lay and ecclesiastical patrons required. Not surprisingly, those offered by St Giles' changed in this period. Emphasis upon the daily care of the sick was gradually superseded by the hospital's liturgical functions, which meant that more money was spent on them and less on the poor. Of course, these innovations could benefit patients, not least because spiritual medicine was at the heart of the hospital. None the less, as time went on, we can detect a growing sophistication on the part of potential benefactors, who demanded that the right sort of paupers (no lustful beggars allowed!) should be saying prayers on their behalf. They wanted the welfare of their souls to be at the top of the religious agenda, and now became just as concerned with the quality of prayers as the quantity. But why?

[top]

What was the Black Death?

In 1348, there was a devastating outbreak of plague in England, now called the Black Death, which is estimated to have killed about 1/3 of the population. Severe outbreaks continued at regular intervals at a national and local level until 1665. Like many other cities, Norwich was badly affected by these epidemics. Its population fell from about 25,000 in the 1330s to fewer than 9,000 by the 1370s, and stagnated until the start of the sixteenth century. The impact of such dramatic losses was considerable, both on the economy and on the way people thought about death.

Understandably, losses on this scale fixed people's minds on the afterlife, and heightened the sense of vulnerability felt by the rich - that is, those who would find it the hardest to enter the gates of Heaven. Indeed, thoughts of mors improvisa (sudden death) concentrated the mind with unusual clarity upon the importance of spiritual health and especially upon the need for masses and prayers to speed the soul through Purgatory.

The Black Death, and the fear of Purgatory, also affected hospitals, not least in driving forward a number of reforms and building programs. Whereas God, Christ and the Virgin had been the principal focus of religious devotion in hospitals before the Black Death, they and the whole company of Heaven were subsequently invoked in an incessant round of prayers and masses. What is more, as God was likely to turn a deaf ear to the prayers of the impious and unworthy, patrons began to insist that the patients should be docile and upright individuals, innocent, as far as it was ever possible, from the stains of sin.

The Black Death also prompted investment in liturgical items. John Derlyngton, who, if we remember, helped fund the bell tower, may also have commissioned the hospital's illuminated processional.

[top]

What was the Processional?

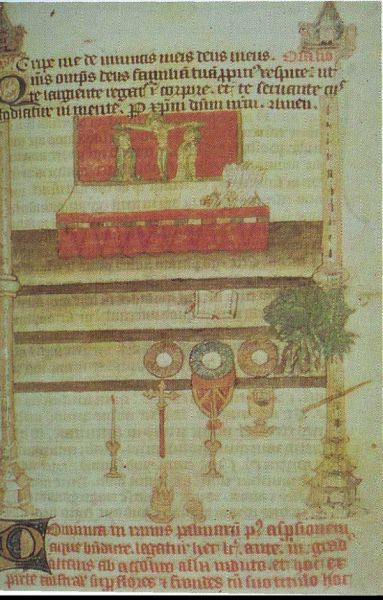

A medieval processional was a small, portable book containing music for the liturgical ceremonies. St Giles' processional is now unique among medieval service books in providing colour diagrams explaining how nine major liturgical ceremonies should be performed. It gave clear directions to the participants, who would have included choristers, candle-bearers, censers and crucifers, as well as the officiating priest and his assistants.

Let's take a closer look...

Pictured above: British Library, Add. MS 57534, f. 32r - diagram from the hospital's processional.

The above diagram, 'The blessing of branches on Palm Sunday', shows the flowers and foliage given by the clergy on the high altar and the offerings of the laity on its steps. The officiating priest, designated by a blue tonsured head above a red and gold cope, is flanked by his deacon and subdeacon. Other participants are denoted by the relevant symbol - service book, candles, crucifix, holy water stoup, wand and censer.

The painting of the Crucifixion on the altar may, perhaps, be similar to one actually in use at the hospital, and would certainly have been appropriate, given the concept of Christ as Physician, discussed above. Moreover, it may be that the Despenser retable, now on display in Norwich Cathedral, was actually commissioned for the hospital.

Pictured above: 61F9 - painted retable in St Luke's Chapel, Norwich Cathedral

All this evidence reveals the extent to which, between the mid-thirteenth and mid-sixteenth century, Bishop Suffield's hospital changed. It grew much grander, with its church, cloisters and tower. Less emphasis was placed upon the founder's original intention of caring for the resident sick and poor and increased attention was given to the daily liturgical round. Yet even greater changes were about to happen.

[top]