Medieval

Medieval

Background

Background

- Introduction

- What was a medieval hospital Like?

- Why was the Soul so Important?

- Why did you have to Confess?

- What Medicine was there and were there any doctors?

- What was the Mass and why was it so Important?

- How Often did Religious Services take Place?

- How Important was Singing and Music?

- What Physical Treatment was Offered?

- Who cared for Patients?

Medieval History

Buildings and Changes

Introduction

This part of the site is designed to provide you with a basic introduction to medieval hospitals and medieval medicine in general. You will find examples throughout, and links to other parts of this site where you can access more information.

What was a medieval hospital Like?

There were over a thousand hospitals in medieval England, but they did not look like any hospital you might know, nor did they care for patients in a way that you would recognise today. Indeed, the medieval English hospital was an entirely different creature from its modern descendent.

Firstly, they had no professionally trained doctors or surgeons, and seldom was any 'medical' treatment offered. Indeed, medieval hospitals in England were not founded to provide medical treatment as we understand it, and people with apparently incurable or contagious diseases were often denied entry. However, as we shall see, this does not mean that patients were neglected or that standards were woefully poor.

Secondly, there were four main types of institutions for the poor and sick:

- Leper houses

- Hostels for pilgrims

- Institutions for the sick poor (such as the Great Hospital, or St Giles', as it was then known)

- Almshouses

All these types of 'hospitals' varied in size and means, but what each had in common was religious life and spiritual care. Contemporaries found it almost impossible to distinguish between hospitals and houses of religion. This might help to explain why you could easily mistake St Giles' for a medieval church. In fact, when the nearby church of St Helen (on the opposite side of the road, where there is now a playing-field) was granted to the hospital in 1270, the master and brethren of the hospital persuaded the bishop to have it demolished to that they might incorporate a new church inside the hospital itself. By the late fourteenth century, an impressive chancel had been built (it was finished around 1383), and a bell tower added next to the infirmary hall. This complex now served as the local parish church.

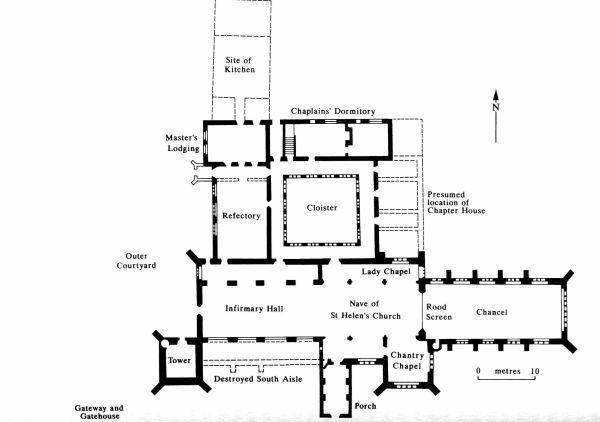

Take a look for yourself. If you examine the plan of the hospital, you can easily see that it shares many similarities with a church. It has a nave, chapels and chancel.

As you can also see, the standard layout of open ward hospitals, such as St Giles', housed the patients under one roof, and ensured that anyone lying in the infirmary ward was in sight - or at least hearing - of the chancel. In fact, the physical body of the hospital was firmly united with its spiritual 'soul'. This was for a very good reason:

[top]

Why was the Soul so Important?

People in the Middle Ages thought that the body and soul were joined, and that health depended on them being in harmony. Physical infirmity, for instance, was often regarded as a sign of some deeper spiritual wrongdoing (such as gluttony or lust). In short, disease and illness could well be a punishment for sin.

There were two types of sin: Original Sin, and personal sin.

Original Sin: this was inherited from Adam and Eve. When Adam and Eve lived in Paradise, everything was perfect - there was no disease, sickness or pain. However, once they had bitten into the apple, everyone suffered. The fateful event, known as the Fall, incurred punishment for them and all their descendants ranging from death, epidemics and illness to the pains of childbirth and menstruation. The consequences were felt by everyone, rich or poor, young or old.

The burden of Original Sin had been lightened, however, by the sacrament of baptism and Christ's sacrifice on the Cross. The Church taught that Christ (who Himself was described as a physician), had died on the cross to save mankind from eternal damnation in hell.

If you look closely at the roof bosses in St Giles', you will see that some depict events in the life of Christ. This boss, for instance, was from Bishop Goldwell's chantry, and depicts the Ascension. Christ's feet are still visible as He ascends through the fan vaulting of heaven.

Pictured above: The Ascension of Christ. Photographer: Bruce Benedict

Personal sin: this was self-inflicted, and, in contrast to Original Sin, varied from individual to individual. The worst, and most likely to be punished, were generally known as the Seven Deadly Sins (pride, envy, gluttony, lust, anger, greed and sloth).

The Church divided sin into two principal categories: 'venial' which were relatively minor, and could be forgiven, and the more severe 'mortal' sins, which, when committed, incurred the threat of eternal damnation unless they were absolved through confession.

[top]

Why did you have to Confess?

In 1215, leaders of the Church (headed by the Pope) met at what is now called the Fourth Lateran Council, and declared that those personal sins committed during life had to be confessed on a regular basis in order to achieve salvation. They expected people to do this at least once a year. In a celebrated ruling (cap. 22), the Council also declared:

As sickness of the body may sometimes be the result of sin ... so we by this present decree order and strictly command physicians of the body [i.e. doctors], when they are called to the sick, to warn an persuade them first of all to call in physicians of the soul [i.e. priests] so that after their spiritual health had been seen to they may respond better to medicine for their bodies: for when the cause ceases so does the effect.

(See http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/lateran4.html for a full copy of the text)

Since sin manifested itself as disease in human beings, the priest, described by the Council as a "skilled doctor", was expected to hear confession and to give the sinner ("sick person") a suitable remedy so that he or she could recover. Sin positively reeked of disease, and just like an epidemic, it could 'infect' others. The contagious nature of sin was so feared that many patrons of medieval hospitals (including Bishop Suffield) stipulated that someone should be at hand to hear a patient's confession before he or she was allowed inside.

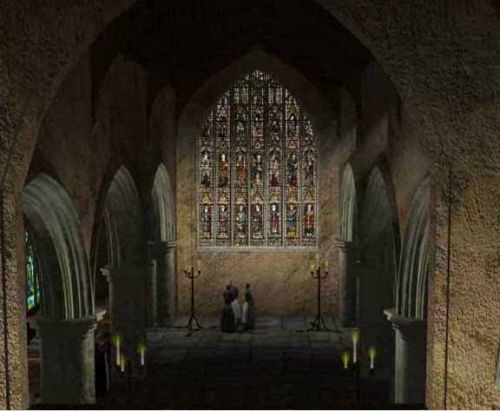

Pictured above: The medieval infirmary hall of St Giles' - in such a religious environment, it was essential to keep the ward free from any spiritual infection.

Demanding confession on entry may seem strange to us today, but we too live in fear of bugs, such as MRSA, infecting hospital wards. What patrons were doing was trying to keep their hospitals clean and free from disease, and instead of hand washes there was confession - the best kind of spiritual detergent known at the time.

Apart from any spiritual benefits confession may have had, it almost certainly imparted some physical improvements due to the psychosomatic effect of relieving the mind from any burden, or guilt, which may have been causing stress and worry.

[top]

What Medicine was there and were there any doctors?

Unlike today, patients in a medieval English hospital generally had to rely on herbal preparations rather than expensive drugs, and surgeons did not operate on patients. In fact, the latest academic research has found that most medieval hospitals were religious institutions where spiritual health was given precedence over that of the body. Of course, as we have already seen, this made perfect sense in a world where sin and disease went hand-in-hand - if you treated the soul, then you treated the body. Indeed, spiritual medicine was thought to be very effective, and it did not require any professional doctors.

Once again, this may be hard for us to comprehend (we would find it odd if, when admitted to hospital, we were told to pray!), but we need to realise that there were very few trained doctors and a comparatively small number of surgeons in medieval England. What is more, they were expensive, and even if you were able to afford their services, the treatment could sometimes be very painful. Instead, patients were offered a consoling regimen of confession and prayer, devised and implemented by the Church. This was provided on a twenty-four hour basis, and centred on the Mass. Hospitals were, moreover, intended for the poorer members of society; those who could pay were treated at home.

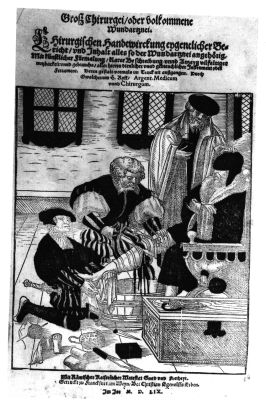

Can you imagine having your leg sawn off without anaesthesia? Indeed, scenes such as that pictured below would have been familiar at the Great Hospital after the arrival of the master surgeon, John Porter, in 1547. He was retained for a substantial fee, and, like the surgeon in the picture, he would have been overlooked by a Protestant priest. Indeed, this provision marked one of the many new departures in the post-Dissolution history of St Giles'.

[top]

What was the Mass and why was it so Important?

The Mass lay at the heart of hospital life, and took place at the high altar, in full view of patients lying in their beds. The Mass comforted the sick with a nourishing elixir of health, and, as we shall see, sped the souls of anxious patrons through the torments of Purgatory.

At the heart of the Mass was the revelation of the body of Christ. He was then often described as thought of a physician - a very powerful physician who had died on the Cross to save mankind. The Catholic Church taught that, during Mass, the bread (often called the Host) and wine were transformed in a process known as Transubstantiation into His body and blood.

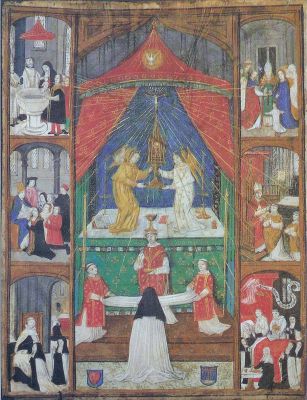

Pictured above: Museum of the Potterie Hospital, Bruges - depiction of a nursing sister about to take communion.

This dramatic event was thought to have miraculous powers, which included healing the body and saving the soul. It was so powerful that merely witnessing the Elevation of the Host (the moment that the priest lifted up the transformed for everyone to see) was thought to wash away sin.

As another ruling of the Fourth Lateran Council made clear, the body and blood of Jesus Christ:

Are truly contained in the sacrament of the altar under the forms of bread and wine; the bread being changed by divine power into the body, and the wine into the blood.

(See http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/lateran4.html for a full copy of the text)

The Roman Mass which, by the middle of the eleventh century, had taken a form that, for Catholics, remains essentially unchanged to the present day, was itself divided into two parts: the Proper, which varied according to the day in question; and the Ordinary, in which the ritual remained more or less unchanged. The Ordinary included five chants: Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Benedictus, and the Agnus Dei.

[top]

How Often did Religious Services take Place?

We are used to our superstores being open twenty-four hours a day, and things were not so different in the Middle Ages - religious services took place from daybreak to sunset (and after as well!). If a patron demanded it (and he or she often did), at least one Mass and the eight Offices of the opus Dei (Latin for 'work of God') were performed daily. The Daily Offices were a feature of those hospitals which followed a monastic or quasi-monastic rule, and were fixed at the following times:

| Nocturns (later called Matins) | Midnight |

| Lauds | Daybreak |

| Prime | 6 a.m. |

| Terce | 9 a.m |

| Sext | Midday |

| None | Between 3 and 3 p.m. |

| Vespers (later evensong) | 6 p.m. |

If you read St Giles' foundation charter, you will see that Bishop Suffield provided the hospital with four 'honest' chaplains (fully ordained priests), a deacon (an assistant clergymen to minister) and a subdeacon (this was the person who carried the chalice with the wine to the altar). The rule to which they submitted was modelled upon that of the Augustinian canons. Under this particular rule, excessive liturgical ritual was discouraged to permit more time for charitable works. Nevertheless, Bishop Suffield stipulated that the master and chaplains of his new hospital were bound to:

Rise in the morning at dawn when the big bell strikes ... and enter the church together ... They shall sing matins and the other hours with due chant and measured delivery, and immediately celebrate the mass of the day solemnly.

(Click here to read the charter in full)

[top]

How Important was Singing and Music?

In larger hospitals, which could afford it, the Mass and Offices were often accompanied by the heavenly sound of music. This music, however, was not like anything found on the charts today. Instead, it was designed for the glorification of God, and its words were based on passages from the Bible. In those institutions with generous budgets, large choirs, staffed by trained choristers, sang complex music, sometimes accompanied by an organ.

To hear an example of this type of medieval music, click on the following external link and press 'listen':

http://www.mtraks.com/artist/the_rose_and_the_ostrich_feather/track/391765-salve_regina

Music played a fundamental part in the life of medieval English hospitals, not just the rich ones, and was far more than a mere background sound. Music was thought to offer considerable physical benefits: it could raise the spirits, cheer the soul and help reduce stress. It must have been important at St Giles', because successive masters and patrons spent considerable sums of money on providing the hospital with musical resources. By the late 1390s, for instance, the hospital boasted a greatly enlarged chancel equipped with canopied choir stalls - the acoustic of which must have been very impressive.

It also owned excellent instrumental resources, including a 'great' and 'little' organ. The latter stood in the Lady Chapel, where it would have been used to accompany the elaborate voices of the choir singing masses of the Blessed Virgin Mary (as the mother of Christ, Mary, like her Son, was thought to possess considerable healing powers).

Pictured above: The coronation of the Virgin in the chantry chapel roof. Photographer: Bruce Benedict.

Many richer hospitals ran choirs, and employed a singing master. He would have instructed and disciplined boys in the choir. St Giles', for instance, cared for seven poor scholars who sang in its choir. The boys, who were selected on merit from local song schools, were to receive a daily meal during the school terms until they had achieved a good grasp of Latin (essential if they were to sing the opus Dei). By the late fifteenth century, the choir was set on a yet more formal footing. At this time the hospital retained the services Richard Frevylle, who found employment as both organist and master of the choirboys. His contribution may have been considerable, as he had been senior boy (by 1494) at St George's Chapel, Windsor, an establishment famous throughout England for the quality of its singing.

Almost all the hospital's books were destroyed during the Reformation, but we can tell how impressive its musical resources mist have been from a beautifully illuminated processional (a guide to the performance of liturgical ceremonies). St Giles' processional is now unique among medieval service books in providing coloured diagrams explaining how nine major liturgical ceremonies should be preformed. To find out more, click here.

Pictured above: British Library, Add. MS 57534, f. 57r - depiction of the paschal candle on Easter Saturday.

[top]

What Physical Treatment was Offered?

The medieval English hospital adopted a holistic approach to healing. The fact that there were no professionally trained doctors or surgeons does not mean that patrons ignored the physical needs of their patients. As we have already seen, spiritual medicine was deemed to be very effective in curing the body of disease. None the less, patrons also ensured that their patients enjoyed bed rest in warm and relatively clean surroundings (cleanliness and godliness went hand-in-hand in the Middle Ages), and were fed with a regular supply of fresh food and drink, often grown and cooked on the premises.

Residents of the Sherburn hospital, near Durham, which was one of England's largest foundations for lepers, were fed with meat, fish and cheese, clothed in clean linen and woolen cloth, and kept warm with fires of peat and wood. At St Anthony's hospital, London, which was far richer, patients and staff consumed a wide and varied selection of food, including fresh salmon, turbot, shrimps, plaice, pork, capons, beef, geese, veal, rabbit, damsons, pears and apples.

Pictured Above: Archives of the Hospital of Notre Dame, Tournai, foundation charter of 1238 - patients enjoyed a good, if basic, diet.

St Giles's hospital also provided for its patients, who enjoyed the relative comfort of 30 beds with "mattresses and sheets and coverlets for the use of the infirm poor" (click here to read the foundation charter). As was the custom, however, these were shared. Its gardens produced vegetables and herbs that were frequently used in the kitchens. Flowers and herbs were also grown for the production of scented candles; and, during the fourteenth century, surplus apples, pears, leeks, garlic, onions and honey were sold on the open market for a modest profit.

Thirteen additional paupers were also to be fed daily, their meal consisting of good bread and drink (probably ale), and one dish of fish or meat. Occasional handouts of cheese or eggs provided a welcome change of diet. Although these doles were distributed outside the gates of the hospital during the warmer summer months, the paupers were permitted to eat by the fire inside the hospital during blizzards, rainstorms and otherwise miserable winter weather. Since, in 1249, many people faced starvation, Suffield's charity made a difference between life and death.

[top]

Who cared for Patients?

Sisters and lay nurses played a vital role in providing patients with a physical environment of care, even if their contribution has not always been fully appreciated by historians.

For a start, nurses not only made the beds but also laundered the bedding: at the Hôtel Dieu, Paris, upwards of 900 sheets were washed every week by the sisters and novices who served in the two laundries. In this image, the frontispiece to Jehan Henry's Livre de Vie Active, produced in the late fifteenth century, you can see in the scene to the right novices handing out the wet sheets.

Pictured above: Musée de l'Assistance Publique, Paris.

At St Giles', Bishop Suffield decreed that there should be three or four women (or 'sisters') in the hospital to take:

Good charge and care of all the infirm and other sick lying there. They shall change the sheets and other bed clothes as often as necessary, and serve them humbly in necessary things as far as they are able...

(Click here to read the foundation charter)

The nurses who worked in the hospital may have been corrodians: that is, they may have handed over their cash or possessions, or settled property on the hospital, in return for receiving accommodation, food and perhaps a small weekly sum for the rest of their lives. In 1309, for example, a corrodian, the widow Mary de Attleborough, exchanged her late husband's property in Seething for a permanent residence just outside the gates of St Giles'.

Although women were welcome as nurses, Walter Suffield did not entertain the idea of having female patients or any other residents. The sexual temptation which they presented was, in his opinion (and that of the Church), likely to disturb the daily liturgical round. Furthermore, if any member of the community committed sinful acts in what was meant to be a pure spiritual environment, he would risk infecting the hospital ward with a dangerous pollutant.

These problems would, Bishop Suffield hoped, be avoided by employing only women aged over fifty years or thereabouts who, it was thought, would be beyond encouraging (or worse still, engaging in!) sexual irregularity.

[top]