Introduction

This part of the site is designed to provide you with a brief guide to the period of change and reform which occurred in the mid-sixteenth century. It will explain why Henry VIII had his eye on the Church, and what the Reformation was.

[top]

What was the Reformation?

During the Middle Ages it was understood that the head of the Church was the Pope, and the head of the State was the king. It was a period when the Church and State (like the soul and the body) were inseparable. It was also a time when the Church permeated every aspect of daily life; when kings looked to the Church for spiritual and political guidance.

Under Henry VIII, however, all this was to change. In 1534 Henry declared himself the head of the English Church in the Act of Supremacy. This was in part a result of his failed attempts to secure papal approval for his divorce from Katherine of Aragon. It became clear that the Pope would not grant a divorce, and, if Henry wanted a new wife, he would have to defy the Holy See. More to the point, however, was the fact that Henry needed money, and by taking control of the Church of England, an institution that was rich in land and property (particularly that of the monasteries), he could solve his financial difficulties.

However, the Act also has to be seen in terms of Henry's efforts to reform the Church of England. The Church was increasingly under attack in certain quarters on charges of poor administration, and the influence of Rome meant that sweeping change was out of the question. There was, in addition, a growing demand among many influential figures for an end to certain beliefs and practices that were seen as superstitious or misguided. By breaking with Rome, and declaring himself as the supreme head of the Church, Henry found a solution to these problems.

THE ACT OF SUPREMACY (1534)

Albeit, the King's Majesty justly and rightfully is and oweth to be the supreme head of the Church of England, and so is recognised by the clergy of this realm in their Convocations; yet nevertheless for corroboration and confirmation thereof, and for increase of virtue in Christ's religion within this realm of England, and to repress and extirp all errors, heresies and other enormities and abuses heretofore used in the same, Be it enacted by authority of this present Parliament that the King our sovereign lord, his heirs and successors kings of this realm, shall be taken, accepted and reputed the only supreme head in earth of the Church of England called Anglicana Ecclesia, and shall have and enjoy annexed and united to the imperial crown of this realm as well the title and style thereof, as all honours, dignities, preeminences, jurisdictions, privileges, authorities, immunities, profits and commodities, to the said dignity of supreme head of the same Church belonging and appertaining.

And that our said sovereign lord, his heirs and successors kings of this realm, shall have full power and authority from time to time to visit, repress, redress, reform, order, correct, restrain and amend all such errors, heresies, abuses, offences, contempts and enormities, whatsoever they be, which by any manner spiritual authority or jurisdiction ought or may lawfully be reformed, repressed, ordered, redressed corrected, restrained or amended, most to the pleasure of Almighty God, the increase of virtue in Christ's religion, and for the conservation of the peace, unity and tranquility of this realm: any usage, custom, foreign laws, foreign authority, prescription or any other thing or things to the contrary hereof notwithstanding.

[top]

What happened next?

After Henry had declared himself head of the Church of England, all regular clergy and members of institutions such as St Giles', had to take an oath, denouncing the Pope and swearing allegiance to the King. Not forgetting the wealth of those institutions which now came under his personal jurisdiction, he also imposed taxes on the clergy. In 1534 he decided to impose a new annual tax of 10% the income from all church lands and offices. So that he knew how much the property was worth, and how much to expect, he ordered a great survey of ecclesiastical property, known as the Valor Ecclesiasticus. This applied to the larger church-owned hospitals, many of which were sorely decayed and had abandoned their charitable work. The entry for St Giles' in the Valor records that only six short stay patients and four almsmen were being cared for.

Henry then set about confiscating the property of England's monastic institutions. This process is now called the Dissolution. St Giles', however, was not among the hundreds of hospitals which succumbed -it evidently satisfied the commissioners that it was still a viable charitable institution but more importantly commanded the support of the rulers of Norwich. It is because St Giles' did not fall victim to the Dissolution of the Monasteries that its valuable archival evidence was not destroyed or lost and its buildings were not converted to other uses.

Yet although the hospital might have avoided dissolution, it was not immune to the changes which affected every religious institution in the country. Because most hospitals were primarily houses of religion, they were particularly susceptible to changes in the spiritual climate. What, for instance, would happen when if the doctrine of purgatory was firmly and finally rejected? What would be the point of St Giles' then?

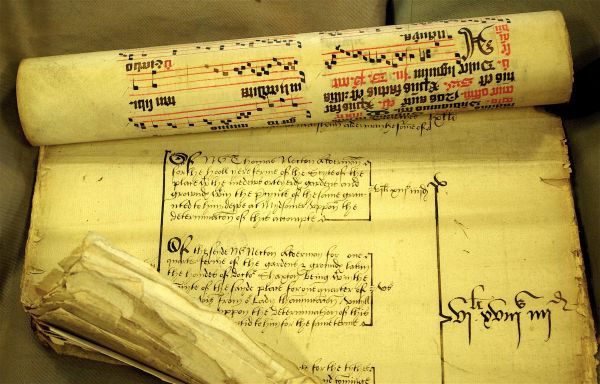

Some idea of the impact of the Dissolution upon St Giles' may be gained for the fact that the first accounts prepared by the new keepers (click here to find out more) were wrapped in pages torn from medieval service books. Paper accounts for 1548-9 and 1550-1 are, for instance, bound in parchment leaves ripped from one of the hospital's fifteenth-century missals, recording the sequences for four votive masses, including one for the Blessed Virgin.

Pictured above: NRO, NCR, 24A, GH Accounts Box, 1548-5

| Out | In |

| Abolition of Purgatory | Emphasis on good deeds on their own merits, rather than a means to salvation |

| Saints/intercession/Blessed Virgin Mary | Christ alone |

| Transubstantiation (The doctrine that the substance of bread and wine change into the body and blood of Christ occurring in the Eucharist) | Consubstantiation (The doctrine that the substance of the body and blood of Jesus coexists with the substance of the bread and wine in the Eucharist.) |

[top]