Introduction

This part of the site is designed to provide you with a brief guide to the period of change which occurred between the 1530s and the seventeenth century. It will explain why the hospital was now called 'God's House', how patients were treated, and what impact Kett's rebellion (1549) had upon the fabric.

[top]

Why did the hospital change its name?

When Henry VIII died in 1547 the then master, Nicholas Shaxton, surrendered the hospital to the new Protestant monarch, Edward VI. The residents must have waited anxiously to learn their fate.

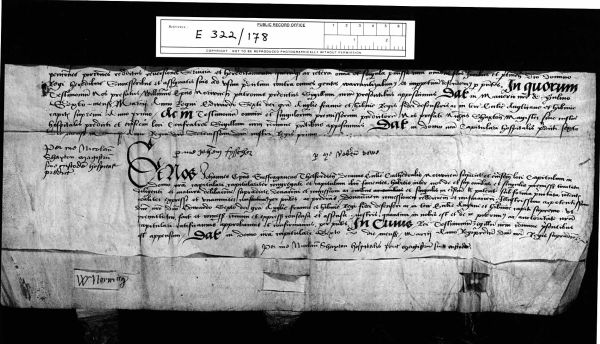

Pictured above: PRO, E22/178 - the last part of the formal deed of surrender, dated 6 March, 1547.

The city fathers, however, were sufficiently astute to recognize the important role St Giles' hospital might play in caring for the city's poor (who now posed a serious social problem). Perhaps in an attempt to retain the loyalty of the people of Norwich, or simply in response to the citizens' persistence, Edward VI succumbed to local pressure and returned the ownership of the hospital and all its possessions, land and property to the corporation. But the dedication had to change, because the doctrine of purgatory - and with it the idea that saints could help people in life or the next - had to be abandoned. From then on St Giles' hospital became known as 'God's House', or the 'House of the Poor People on Holme Street'. Returning to the founder's original desires, the hospital again began to prioritise charitable work in the community.

[top]

What were the arrangements of the Refounded Hospital?

Under the new arrangements, the civic authorities agreed to support forty male and female residents in the refounded hospital. Permanent domestic staff consisted of a curate and minister for the poor, a 'visitor' (who was also a priest) to prisoners held in the Guildhall, a schoolmaster and one or two ushers or assistants, a male keeper or master who had overall responsibility for the running of the establishment, four female nurses, a steward who looked after provisions for the poor, and a person who combined the tasks of a cook, baker and brewer.

The 1547 charter, which was drawn up when the corporation took over the hospital, stated that the four women were to "make the beddes, washe and attend upon the seid poore persons".

Click here to read the refoundation charter.

[top]

What changes were there?

Between the 1540s and the start of the seventeenth century, God's House was transformed from a religious institution into a hospital with limited medical care for the elderly and education facilities for at least twelve poor children.

The appearance of the hospital changed as its functions altered. For example, the chancel and medieval infirmary were separated from the nave by the insertion of two walls extending from floor to ceiling, which allowed the easier segregation of men and women. The symbolic significance of placing women in the former chancel would not have been lost on contemporaries: the chancel was the most sacred part of the church and, in accordance with medieval Catholic beliefs, had been reserved for priests alone. Protestants were less sensitive to such matters. Following the erection of these walls, the men's ward (in the old infirmary) and women's ward (in the former chancel) were divided into upper and lower storeys. Chimneys were inserted, with hearths to provide better heating.

Pictured above: One of the women's cubicles which were not phased out until the 1980s. Photographer: C. Bonfield.

[top]

How were patients cared for now?

For the first time in its 300-year history, God's House employed medical practitioners. Medical staff on a permanent, or semi-permanent retainer consisted of a barber (who let blood), a surgeon and a bonesetter, together with specialists employed on an ad hoc basis. One of the more unusual entries in the archives even records a payment of 2s. 8d. made in 1577-1576 'to Mary Cole one of the pore women in th'opsitall for a stylt after her leggs was sawen off'.

Special foodstuffs and medicines, which included wine and cinnamon, were also purchased for sick residents. Bread and ale were produced on the premises, and salted fish, particularly herring, and hard cheese were also consumed in large quantities. A limited amount of dairy produce may have been available from the 'milch-cow' kept in the hospital meadow. As had been the case in the Middle Ages, the hospital continued to grow its own fruit and vegetables.

[top]

What about Kett's Rebellion, what happened?

The uprising now known as was instigated by Robert Kett in 1549, as part of a series of popular protests mounted in support of social, agrarian and economic change. During the protest, which at one point witnessed the arrival of an army of insurgents several thousand strong on St Leonard's hill, just across the river from the hospital, the south aisle of the infirmary hall was destroyed. The hospital was looted as the rebels fought their way along Holme Street, now called Bishopgate, on their retreat out of the city.

The trail of destruction comprised nine tenements, two messuages and three houses in Holme Street, and a tenement in Conisford. However, all was not lost and the hospital continues to stand to this present day, minus the south aisle! These dramatic events did, however, have one significant outcome. Having originally intended to move the city's grammar school to the hospital, the rulers of Norwich decided to locate it in the Carnary Chapel by the Cathedral. This is still the site of Norwich School, which might otherwise have begun its life in the chancel of St Giles' hospital.

[top]